|

Ferns and allies Gymnosperms

Angiosperms Introduction A draft checklist of the trees and shrubs of Kern County was initially prepared as a result of teaching a short course on the subject for the Levan Institute. Because A Flora of Kern County, California by E. C. Twisselmann with a key to the flora by L. Maynard Moe (1995, CNPS, Sacramento) was out of print, it was also decided to create an identification manual. The work is still in progress; however, examples are provided here, subject to further revision. Included are descriptions and keys to genera and species to the following highlighted links on this page and to species on separate pages where images of species inside and outside the County flora are presented. Descriptions and keys to the species are presented after (below) images. Asterisk denotes introduced families or genera that might occur in Kern County. Genera in parenthesis are the only genus of shrubs or trees for that family in Kern County.

Methodology and Terminology Species are included if reported in the literature and/or databases to occur in Kern County. Those that are questionable are in normal type, those native and clearly recognized as occurring in the County are in bold. Non-native species are also in normal type denoted by an asterisk. The species are classified in families and genera most often according to the arrangement in JM2, but not always. Keys are based on those found in floras and other literature and from reviewing images on the Web and photographs obtained by the author. There are many cases where it appears that species are not clearly defined in the literature. Surprisingly, this can include some of our most common species such as California juniper vs. Utah juniper, ephedras, buckbrush (Ceanothus cuneatus vs. C. vestitus). In such cases, a discussion usually follows. References commonly employed are often abbreviated and cited without date of publication. For example, JM1 refers to the first edition of the Jepson Manual; MCV2 refers to the 2nd edition of the Manual of California Vegetation, and Abrams, published in four volumes, is simply cited as Abrams, as also Twisselmann for his flora of Kern County. The complete citations are given in the list of References below. Nomenclature for author citations differs from what is usually done. The common practice is to cite the scientific name followed by the author(s) who first described the species, and if it has been reclassified then the original author(s) is placed in parenthesis followed by the current author. Author names are often abbreviated according to a standard reference, but in this treatment full last names are given with or without initials, depending on whether the author’s name is common for different people (e.g., Jones). Additionally, the year in which the species was first described is also included as well as the current accepted name. For example, California buckeye, currently Aesculus californica, was first described in the genus Calothyrsus as Calothysus californica by Spach in 1834 and later placed in Aesculus by Nuttall in 1838. This is cited as Aesculus californica (Calothyrsus californica Spach 1834) Nuttall 1838; the bold font indicating it is a native that occurs in Kern County. Other synonyms are cited if commonly found in other floras of California, especially Twisselmann and Munz. Not all synonyms are included. Abrams and the Intermountain Flora are good references to find a more complete history of the nomenclature for a species. The authors names and dates are not included in the literature cited. Data for descriptions were usually taken from many references, often selecting the highest and lowest values for measurements. Ideally specimens in a herbarium for Kern County should be consulted, but this was not practical since there is no major herbarium in Kern County.

Technical terms are avoided as much as possible,

especially for leaf shapes and flower arrangements (inflorescences), but occasionally

mentioned in parenthesis. Elliptical, egg-shape in outline—widest at the mid region—is

employed as a central reference point for the shape of a

structure such as a leaf. For example, instead of

describing leaves as elliptic to oblanceolate or lanceolate, leaves are described as elliptical or widest above or below the

mid region. Other substituted terms or descriptive text include heart shaped for cordate,

and leaves with parallel margins for most of their length, which

technically in the botanical literature is referred to as oblong if shorter than 10 times longer than

wide, or linear if 10 or more times longer than wide. Instead of

referring to an inflorescence as a raceme, spike, panicle, corymb, or by

other terms, the term scape is applied to any leafless flower bearing

stem and its branches, or scape may have reduced leaves or bracts, and

branching of the scapes is then described.

Scape technically

is a leafless flowering stalk from stem-less (acaulescent) plants, often

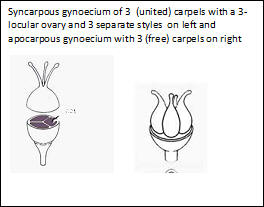

arising from the center of a rosette of leaves at the base. However, technical terms are employed in regard to floral parts and fruit types. Gynoecium is a technical term for the female reproductive part of the flower, the basic unit of which is a carpel, a term that originated for that of the fruit. The carpel includes the ovule (seed) bearing portion of an ovary (the placental region) along with the style and stigma. Flowers may consist of multiple distinct or fused carpels. When carpels are united they appear as a single unit, referred to as a pistil, consisting of an ovary, one or more styles and stigmas that correspond to the number of carpels that form the single ovary. When the styles and their stigmas appear as one, the number of carpels, if more than one, may be determined by counting the placentae in a cross section of the ovary, usually occurring in longitudinal lines along a central axis that may divide the ovary into chambers, or along the walls of the ovary if not chambered, or may be restricted to the base and apical regions of the ovary. Flowers with a gynoecium of one carpel is characteristic of the legume family (Fabaceae); those (gynoecia) containing separate (multiple) carpels are commonly seen in the rose family (Rosaceae). Gynoecia with separate carpels are also referred to as apocarpous, in contrast to those with fused carpels, syncarpous. The latter is in further contrast to schizocarpous, one with united or partially united carpels in flower that separate in fruit. The classification of plants into families and genera generally gives considerable weight to gynoecial differences. The term fruit is generally recognized on this website as one or more seeds with accessory parts that aid in their dispersal from the plant as a single unit (Spjut 1994); however, in most of the literature the term fruit—as encountered in botanical descriptions of families, genera and species—is more restrictively applied and usually inconsistent with the definition given in the glossary. For example, in JM1, fruit is defined as “a ripened ovary and sometimes associated structures.” This allows for the popular exceptions such as the apple and strawberry that have a long history of being regarded as fruit even though they include accessory floral parts. This also allows for the fruit of hop-sage (Grayia spinosa, Chenopodiaceae) that has two united “fruiting bracts” (JM2) with wings similar to an elm fruit (Ulmus, samara)—but are not considered part of the fruit in JM1; however, it may be further noted that in JM2 "fruit bracts” are mentioned in the description of the pistillate inflorescence but excluded from the description of the “fruit,” which under the family description (Chenopodiaceae) is referred to as an “achene” or “utricle.” On this web site, the hop sage fruit is regarded a diclesium (di for two + clisto or kleistos for closed) indicating two coverings over the seed(s), one for the mature ovary wall (pericarp), the other for united bracts. Because the bracts are winged like the fruit of the elm, known as a samara, the fruit of hop sage may be further distinguished as a samaroid diclesium (Stuppy & Spjut in prep.). Whether fruit should receive such special names is controversial. Historical accounts on the concept of fruit and its nomenclature can be found in Spjut (1994), and on this website at A Systematic Treatment of Fruit Types. Geographical data were extracted from a number of references and from Internet Sources. Most data on the geographical distribution of species in Kern County are from Twisselmann whose work is cited throughout. Additional data include where the species was collected when first described (type locality), and whether it is recognized by Sawyer et al. 2008, Manual of California Vegetation (MCV2). Generally plants cited in this reference have to be fairly common. In preparing this manual, it is quite obvious that Twisselmann had extensive field knowledge of the County flora. However, he rarely included elevation data so this was added from records in CCH, although it became apparent that many species in Kern County have a wide range in elevation. It should be kept in mind that Twisselmann identified plants using Munz and Keck's A California Flora (1959 and supplement), although he did not always follow their nomenclature (e.g., Diplacus calycinus in Twisselmann instead of Mimulus longiflorus ssp. calycinus in Munz & Keck), and he may have felt that it was not necessary to provide a key, because the Munz flora was considered the standard reference at the time, remaining so until JM1 (1993). However, in some respects Munz appears to be an updated account of Abram's (1923–1951) 4-volume work without the illustrations and detailed synonymy. Abrams work is still an invaluable tool for comparing closely related species descriptions and illustrations. Abram's format makes it easy to see at a glance the differences in species, and Abrams often illustrated key characters. Unlike the JM1 and JM2, discussed below, the arrangement is natural rather than alphabetical. The original Jepson Manual, A Flora of California, like Abrams, was also a thorough accounting of the California Flora, but with only some of the species illustrated. The later Jepson Manuals (JM1, JM2) added more illustrations while reducing descriptions of species to a bare minimum. Obviously, the idea is to have an accounting of the entire flora reduced to a single volume that one can carry in the field. Further reductions in text were made by using abbreviations for geographical data and common words (e.g., "gen" for generally) and plant parts (e.g., st for stem). Students initially may find it difficult to read such keys and descriptions. The main disadvantage in using JM1, JM2 is the nonparallel species descriptions for the sake of brevity. If all the species were illustrated this would make identifications easier. One has to review the key descriptive features in the various steps of the key as well as the species descriptions to be sure whether the presence or absence of character features apply. Those who are fortunate to have a herbarium close-by will have less trouble. CalFlora, Calphotos, and the Consortium of California Herbaria (CCH), however, provide a valuable resource to help offset those who are not as fortunate to have herbarium material for making comparisons. The following keys to genera are arranged by Ferns and fern allies, Gymnosperms, and Angiosperms, with families in alphabetical order.

Key to the Major Groups

1. Flowers present, or evidence of having flowered by the 1. No evidence of flowers, seeds if present in cones, or subtended by bracts.............. 2

2. Shrubs with green broom-like jointed stems, the stems longitudinally

2. Trees or shrubs not as

above, stems if joined fleshy (Allenrolfea)..............................

3

3. Trees, or rarely shrubs (California juniper); leaves awl-like

or persistent on the tree on lower branches, or breaking apart in

the

3. Trees usually with broad leaves, shrubs sometimes with needle to

4. Plant spreading

along the ground, shrub-like or moss-like, usually

4. Plant with erect to

spreading leaves (fronds) from a reddish orange 4. Not an ephedra, fern, spike-moss or conifer..................................... Flowering plants

Ferns and Allies Spike-mosses: Selaginellaceae.......................................................................... Selaginella

1.

Plants with tall erect green fronds; ultimate leaf segments

2. Sporangia in sausage-shaped sori in a line along each side of the

1.

Plants broader than high, the fronds wide spreading; ultimate

Gymnosperms Ephedraceae (Ephedra) 1. Leaves awl-like, scale-like or needle-like.............................................................. 2 2. Leaves predominantly awl-like and/or scale-like........ ................. Cupressaceae 2. Leaves needle-like (spirally arranged or in fascicles) .......................... Pinaceae 1. Leaves mostly blade-like, spreading in one plane......... ......................................... 3 3. Seeds in woody cones............................................................... Cupressaceae 3. Seed berry-like, covered by a red fleshy layer (bract)...................................... 4

4. Seed tightly covered by a greenish layer with purplish specs,

olive-like; reported as far south as Tulare Co............................................. Taxaceae (Taxus)

Cupressaceae (Cypress Family)

Shrubs or trees, deciduous or evergreen; leaves blade-like arranged in

two ranks or awl-like in Key to genera of Cupressaceae 1. Mature leaves awl-like or scale-like....................................................................... 2 1. Mature leaves blade-like, narrow linear................................................ ................. 5

2.

Leaves alternate (spirally arranged); giant sequoia, Sierra Nevada to 2. Leaves opposite or in whorls.......................................................................... 3

3. Seed cones opening

on the tree—like duck bills, falling like 3. Cones round, dispersed by birds or opening upon fire.............................................. 4

4.

Cones born on old branches, brown, divided into hexagonal plate-like

4.

Cones on young green branches among the scaly leaves, covered by

5. Evergreen, cones persistent on trees, coastal redwood. commonly

5. Deciduous, cones breaking apart in trees, bald cypress,

Pinaceae (Cones below are in regard to seed cones, not pollen cones) 1. Cones often not evident except near tops of trees, usually break apart in the trees (branches sometimes break off with cones)................................. Abies

1. Cones usually seen

on the ground under the tree, or may also persist

2. Needles all

solitary and spirally distributed on twigs; cones with

2. Needles in bundles

on short deciduous spur-like shoots, or

|

||||

|

Adoxaceae (Caprifoliaceae). Shrubs or small trees with opposite pinnately compound (Sambucus) or simple, (Viburnum) leaves (northern hemisphere, South America) or perennial herbs with opposite pinnately divided and/or basal trifoliate leaves (Adoxa, Sinadoxa, Tetradoxa); flowers in terminal umbrelliform arrangements (panicles) or terminal spherical clusters (Adoxa) or with many verticillate clusters along a flowering shoot (Sinadoxa), bisexual or mixed bisexual and unisexual female flowers on the same plant, of 5 partially united sepals and petals in woody species, with fewer floral parts in some herbaceous species; anthers 5, or filaments divided into two (semi-stamens) in herbaceous species (monotypic , Sinadoxa); gynoecium syncarpous, 3–5 carpellate, semi-inferior or inferior or superior and 1-carpelled in Tetradoxa; fruit drupaceous. 5 genera ±220 spp; 2 genera, 4 species and 2 varieties in California, only 1 in Kern County, Sambucus, formerly in Caprifoliaceae along with Viburnum.

|

||||

|

Anacardiaceae (Sumac family). Shrubs or trees, often with alternate pinnately divided leaves, or with simple entire leaves; flowers relatively small but numerous on terminal or axillary branched scapes, often crowded, unisexual or functionally unisexual; sepals and petals usually 5 and mostly distinct to near base; stamens often arranged around or between lobes of a disc; gynoecium usually syncarpous, 3-carepllate and 3-locular, or with fewer or more carpels, or with only one functional carpel, ovules 1, seeds thus 1; fruit a drupe or a cypseloid infructarium (Cotinus). Key to genera/species of Anacardiaceae in Kern County 1. Leaves simple......... ........... ........... ........... .................................. Rhus ovata 1. Leaves compound..............................................................................................2

2. Shrubs; leaflets 3(-5)......................................................................................... 3 2. Tree; leaflets >5, 20 or more .......................................................... *Shinus molle

3. Terminal leaflet stalked; fruit brownish white, smooth.. Toxicodendron diversilobum

3.

Terminal leaflet not distinctly stalked, the blade tapered to base;

|

||||

|

Asparagaceae (Asparagus family) Herbs, shrubs or trees often with fibrous stems and rosettes of long sword-shaped rigid to succulent or fleshy leaves (like bunch grass), the leaves clustered basally or aerially at the ends of trunks which may be reduced to ground level, and with parallel veins; flowers often numerous on leafless simple to branched scapes, frequently in umbellate or head-like arrangements, densely crowded to lax, often drooping, often fleshy, often white or blue, occasionally yellowish or red; tepals usually 6 in number; gynoecium syncarpous, 3-carpellate, inferior to superior, style mostly undivided except near apex; fruit baccate or capsular. Woody plants previously classified in Agavaceae, or with the herbaceous Liliaceae, which is being divided into numerous families, and in which its genera are frequently reshuffled among the revised family arrangements. Asparagaceae genera in Kern County include bulbous herbaceous Themadaceae genera of JM2 (Brodiaea, Bloomeria, Dichelostemma, Muilla, Trieteleia), Agavaceae (Chlorogalum), and woody Ruscaceae (Nolina). Key to woody plant genera/species of Asparagaceae in Kern County 1. Leaves flexible, bending easily, not spine-tipped................................. Nolina parryi 1. Leaves rigid, straight, spine-tipped....................................................................... 2

2. Plants lacking a trunk....................................................... Hesperoyucca whipplei 2. Plants with a trunk............................................................................................ 3

3. Plant tree-like; leaf margins without curly white fibers................... Yucca brevifolia 3. Plant shrub-like, leaf margins with scattered white curly fibers.......Yucca schidigera

|

||||

|

Asteraceae (Sunflower family) Plants with flowers aggregated on a common receptacle in a head surrounded by bracts that often overlap like shingles on a roof, the whole bracteate portion referred to as an involucre, the bracts called involucral bracts or phyllaries. Flower heads generally of five kinds: (1) a sunflower type with ray flowers—also called ligulate flowers (tongue-shaped or strap-shaped flowers, often 3-lobed)—that develop around the perimeter of a receptacle upon which tubular (disk) flowers develop in the central region, which may include receptacular bracts, (2) a disk type similar to the preceding in which there are no ray flowers, but only disk (tubular) flowers, (3) the dandelion (or chicory) type in which are there no disk flowers, only ray type flowers, but since these flowers are not limited to the perimeter of the receptacle, they are commonly referred to as ligulate or strap-shaped flowers, often 5-lobed, (4) heads with morphological different female and male disc flowers on the same or different plants, the females lacking a corolla, and (5) heads divided into subheads, the latter with awl-shaped involucral bracts in several series enclosing one flower, 1–5 subheads that are surrounded by broad leaf-like bracts to form an overhead. Ray flowers are often sterile, or they may be fertile and persist entirely in fruit. Gynoecium of two united carpels, inferior, the ovary unilocular, style terminating in a 2-lobed stigma, Fruit often consists of the pericarpium (achene type, Spjut 1994) that is generally not distinguishable from the calyx except for terminal scales or bristles called a pappus, comparable to terminal parts of a calyx in flowers of other plant families; collectively, the achene and pappus represent the entire fruit regarded as a cypsela, but cypsela in much of the literature is often misapplied to just the achene based on a narrower concept of fruit limited to the calyx portion that covers the mature ovary, because of the ovary's inferior position in the Asteraceae flower; pappus absent in Artemisia, the fruit then an achene. In some genera such as Ambrosia and Hymenoclea, fruits are more conspicuous than flowers; indeed, they develop from an ovary in which the corolla is absent. They may have spines (Ambrosia) or circumferential wings (Hymenoclea). If flowers are past, the receptacle and its subtending bracts often persist in which fruit also may be found. Keys to Genera and Species: I, II, and III

1. Fruit a compound

structure (catoclesium), with spines, or with spiny 1. Fruit a cypsela with scales or bristles, or an achene in Artemisia (no pappus)............................ 2

2.

Plants with milky latex; flowers all strap-shaped, 5-lobed, 2. Plants without milky latex; flowers disc type with or without rays....................................... 3

3. Leaves

heart-shaped to elliptical or blade-like with parallel

3. Leaves often

needle-like (round in × -section) or narrow and threadlike,

Key I (trichotomy)

1. Fruit spiny;

flowers/fruits in a linear array along a terminal

1. Fruit with flaring

skirt-like or fan-shaped wings; leaves needle-like

1. Fruits enclosed

within veiny, leafy-like bracts that are spiny

Key II

1. Flower/fruit heads on long scape-like stems to 15 cm above the

1. Flower/fruit heads not well-separated from leafy stems, either 2. Flowers similar to the sunflower, rays yellow; leaf margins entire................................. Encelia

2. Flowers similar to the aster, rays lavender to purple; leaf margins

3. Leaves divided into narrow to broad lobes............................................................................. 4 3. Leaves entire to toothed along margins................................................................................... 7

4. Leaves narrowly inverse triangular and terminally lobed, usually 4. Leaves lobed along margins, or deeply divided; subshrubs or shrubs....................................... 5

5. Low stiff spiny

shrubs, < 1/2 m high and broad; leaves

5. Subshrubs, not

spiny, the young growth herbaceous or soft-stemmed;

6. Bracts of flower

heads not black-tipped (use hand lens); leaves

6. Bracts of flower

heads black-tipped; leaves divided into long

7. Leaves mostly

broadest near base, triangular to heart-shaped,

7.

Leaves with parallel

margins for most of the length or gradually becoming

8. Involucral bracts

with several or more parallel veins; involucres often 8. Involucres bracts with a single midrib, or midrib not evident..................................................... 9

9. Leaves elliptical;

flowers white within a white to reddish involucre; 9. Leaves heart-shaped; flowers rose to pink, bisexual ............................................... Ageratina

10.

Plants densely leafy at base, mat-like from a woody rhizome, flowering

stems 10. Plants erect shrubs or subshrubs with well developed leafy stems.........................................11 11. Tips of involucral bracts glandular dotted and/or recurved...................................... Hazardia 11. Tips of involucral bracts thickened with a blister-like swelling, erect......................... Isocoma

Key III. 1. Flowers all disc type............................................................................................................. 2 1. Ray flowers present............................................................................................................ 15

2. Plants mostly

leafless, or leaves scale-like, new growth early in the

2. Leaves conspicuous

and persistent on current season growth, deciduous or

3. Intricately branched rounded bushes arising from a short single basal stem............................... 4 3. Shrubs with one or more primary stems arising from the base.................................................. 5

4. Stems rough when

rubbed; receptacle bracts loosely enveloping

4. Stems smooth when

rubbed; receptacle without bracts; occasional

5. Stems whitish green, covered with felt hairs, subshrubs................................... Chrysothamnus 5. Stem green, shrubs... ............................................................................................................ 6

6. Flowers yellow in

bowl-shaped to cylindrical heads; involucral

6. Flowers white in

spherical heads; involucral bracts mostly white

7.... Involucral

bracts 4–6 in a single series, scarcely overlapping along

7.... Involucral

bracts >6, overlapping in imbricate or vertical ranks;

8. Leaves needle-like,

narrow, stiff, thick, inrolled from margins, 8. Leaves flat or folded lengthwise—upwards, ribbon-like to tongue-like................................. 10

9. Bracts of flower

heads (involucral bracts) similar to subtending leaves; 9. Leaves not grading into involucral bracts; flowers yellow to lavender or rose........................ 10

10. Flowers lavender to rose........................................................................................ Pluchea 10. Flowers yellow................................................................................................................. 11

11.

Flowers in

button-like heads (spherical) that are generally solitary and terminal

11. Flowers heads

taller than wide, inverse conical, cylindrical to bowl-shaped

12. Leaves relatively

short, <4× longer than wide; involucre bracts rounded

12. Leaves long and

narrow, >4× longer than wide; involucre bracts pointed

13. Involucral bracts

with conspicuous blister-like glands near 13. Involucre bracts not terminally swollen or thickened............................................................ 14

14. Leaves mostly

round in outline, more tapered to base than to apex (cuneate),

14. Leaves narrow and

thread-like to ribbon-like, >5× longer than wide;

15. Ray florets white to lavender, disc yellow.......................................................................... 16 15. Ray and disc florets yellow............................................................................................... 17

16. Leaves threadlike,

>10× longer than wide, green; involucral bracts

16. Leaves thick, white

hairy especially in youth, <10× longer than wide, widest

17. Cypselae with short white awl-like scales (<2 mm )............................................ Gutierrezia 17. Cypselae with long white capillary bristles (>2 mm)............................................. Ericameria

|

||||

|

Brassicaceae (Mustard family) Herbs or subshrubs with acrid juice and with hairs of various types, or without hairs; leaves usually alternate, simple, entire or toothed to pinnately divided or dissected; flowers radial or rarely bilateral, usually on pedicels of elongated terminal scapes, 4- merous, sepals 4 in 2 opposite pairs, petals distinct and usually clawed, diagonal to sepals, forming a cross from which the family name, Cruciferae is also employed in literature, rarely absent, stamens 6, 2 outer shorter than the 4 inner, rarely fewer as in Lepidium, or up to 16 in Megacarpae; gynoecium with a superior ovary of 2 united carpels ( gynoecium interpretation controversial, Bruckner 2000), the ovary divided by a thin partion (“or commissural septum” ) into 2 chambers that connects to a replum and parietal placentae bearing (1-) 2 rows of ovules, style sometimes evident, stigma entire or bilobed. Fruit variable, commonly known as a silique, silicoid silique if relatively short (width <1/4 length), separating from the partition as two valves along the replum, which persists with the partition, or various other fruit types devlop, which include indehiscent as well as dehiscent types. Cosmopolitian, centered in Mediterranean , ~339 genera, 3800 species. Key to subshrub genera of Brassicaceae in Kern County

Fruit short, round and flattened contrary to the

partition.....................

Lepidium

Caprifoliaceae (Honeysuckle family) Shrubs erect or climbing on other plants; leaves opposite or rarely in whorls, simple, mostly entire; flowers often in pairs, or in small clusters on short flowering axes, 4 or 5 parted (calyx, corolla); stamens 4 or 5, attached to corolla at two levels; gynoecium syncarpous with 2–8 carpels, the ovary inferior with axile placentation, sometimes two ovaries of paired flowers (gynoecia) partially fused. Fruit a baccate dicarpium, or glandoid dicarpium, or baccoid sorosus, or a pyrenarium. Five genera, >200 species in temperate and subtropical North America and Eurasia, 2 genera and 5 species in Kern County. Sambucus formerly Caprifoliaceae, now Adoxaceae. Fruit red, yellow, orange or black................................................................................. Lonicera Fruit white...................................................................................................... . Symphoricarpos

Mostly herbaceous, occasional genera perennial with woody matted bases, rarely diffusely and intricately branched; leaves opposite (sometimes whorled); simple, entire, needle-like to broadly elliptical, short petioled or often clasping stems, the nodes swollen; flowers usually terminal on simple to various trichotomously branched leafless scapes (cymes), solitary on simple scapes, or in branched scapes, the center flower often on shorter pedicels. Flowers parts distinct, mostly in 5’s, petals 5, often lobed or terminally notched, narrowed to claw at base; stamens 5 or 10; gynoecium of 3 to 5 united carpels with a central free column upon which the ovules develop (free central placentation), styles and stigmas 3–5; fruit usually a capsule opening by apical teeth (denticidal capsule). Minuartia nuttallii (Pax 1893) Briquet 1911, a woody species that is listed in CCH as from Kern County, is based on a specimen collected from the Little Kern [River] that is in Tulare County, in the Golden Trout Wilderness. The three species of Minuartia that occur in Kern County are annuals. Key to Genera Capsules with 6 teeth; perennials; leaves needle-like............................... .Eremogone

Capsules with 6 teeth, leaves blade-like, annual or perennial herbs,

|

||||

|

Segregated here from Plantaginaceae where treated by the JM2, the Angiosperm Phylogenetic Group (APG) III, Shipunov (2012, Systema Angiospermarum), and by others (Reveal 2011). Herbs or shrubs with simple or lobed opposite leaves; flowers showy, arranged (inflorescences) in successive leaf axillary (opposite) pairs or bracteate “cymes” (the center most flower of more than two flowers—often in triplets—opening first) along a terminal flowering scape (racemose), or along one side of a terminal elongated flowering scape (spike-like secund raceme); petals united (corolla) into tube with short spreading terminal lobes, generally funnelform, trumpet shaped, or bell-shaped; stamens of four fertile and one sterile (staminoidea); gynoecium of two united carpels with axile placentation, the ovary positioned (superior) above the calyx and corolla. Fruit a capsule, opening along the septa (septicidal capsule), or along the back between septa (loculicidal), or sometimes incompletely septicidal and loculicidal (denticidal). Generally recognized as the Cheloneae tribe with genera Chelone, Chionophila, Collinsia, Nothochelone, Pennellianthus, Penstemon, and Tonella that share features of “cymose inflorescences, staminodes” (sometimes vestigial), “simple hairs and stems with a pith” (Tank et al. 2006). Keckiella, Penstemon, Mimulus, and other genera traditionally placed in Scrophulariaceae have been reassigned to other families based on molecular studies that are given more taxonomic weight by the “Angiosperm Phylogeny Group” (APG) to the overall classification of flowering plants (angiosperms). Since 1998, the APG has increasingly become the deciding force over the traditional morphological classification of plant families weighted on floral morphology. Essentially, molecular plant taxonomists group plants by their genetic relationships. They do this by identifying clades within genealogical trees and then look for morphological characters that best define the taxonomic levels (taxa) of orders, families, genera, etc. which must also show evidence a single (monophyletic) origin (ancestor). The Plantaginaceae, one of many families in the Order Lamiales, formerly included Plantago in the Kern Flora, and two other small genera of herbs found elsewhere in the world. Plantago is identified by having a basal rosette of leaves, terminal spikes of small papery 4-parted flowers, and capsular fruits from which seeds disperse by transverse dehiscence, the upper half coming off like a cap (pyxidium). Plantago genes share a close relationship with those of Veronica (speedwell) and other genera that constitute a tribal clade Veroniceae (APG III). The monkey flower genus, Mimulus, which has lost most of its species to Diplacus (46 spp.) and Erythranthe ( >100 spp.), and which has a similar floral morphology to Chelonaceae as defined here, have been transferred to the Phrymaceae that differs in the absence of a staminode (sterile stamen). Paintbrush (Castilleja) and related parasitic genera have been transferred to Orobanchaceae. Also, the genus Scrophularia (Scrophulariaceae) was found to be less genetically related to other genera formerly included in the family (Olmstead et al. 2001). This led to reassignment of many former Scrophulariaceae genera to the Plantaginaceae. But the similarities between Plantago and the showy Penstemon flowers are not obvious; i.e. also to say they are more similar genetically than morphologically. Although Chelonaceae are treated as a tribe within the Plantaginaceae by most taxonomists, the biogeographical relationships shown in Albach et al. (2005) would seem to justify family status as an alternative to referring Penstemon and other Cheloneae genera to the large heterogeneous assemblage of Plantaginaceae genera (APG III). Key to Genera of Chelonaceae

Fertile stamens all attached at the same level on the corolla, densely

hairy

Fertile stamens in pairs attached at two levels on the corolla,

|

||||

|

Chenopodiaceae (Pigweed family, includes Sarcobataceae) Annuals, perennial herbs or shrubs, often on alkali soil, succulent or not, often with white dandruff-like flakes on the foliage—or appearing like miniature mealy bugs or white flies—formed from aged salt glands; leaves alternate, undivided, often in fascicles, sometimes fleshy or jointed or both; flowers tiny but often conglomerate in axils of leaves or in terminal leafless branched or simple scapes (panicles, racemes, spikes), greenish, unisexual on the same or on different plants (in Kern County shrubs, bisexual in other genera), lacking petals and also sepals in female flowers, bracts usually more conspicuous in female flowers; stamens 5; gynoecium of 2–3 united carpels (syncarpous) with partially distinct styles or stigmas and unilocular superior ovary with basal ovule; fruit usually a diclesium (Spjut 1994, composed of two coverings), the seed free from the mature ovary wall (utricle in much of the literature; utricle pericarpium (Spjut 1994, A Systematic Treatment of Fruit Types), which in turn is enclosed by sepals or bracts. Family Chenopodiaceae included under the Amaranthaceae by the Angiosperm Phylogeny Group, but still recognized by JM2. Key to the Chenopodiaceae Genera 1. Leaves or stems succulent...................................................................................... 2 2. Young stems succulent and jointed; leaves scale-like..................................... 3 3. Leaves alternate.......................................... ............................. Allenrolfea 3. Leaves opposite.................................................................. Arthrocnemum 2. Stems not succulent nor jointed; leaves needle-like in shape, fleshy.............. 4

4. Fruits winged like a gyroscope; shrubs or subshrubs, spiny or not.................... 5

5.

Shrubs with branches ending in a spine-like point; gyroscopic wing

5.

Subshrubs, not spiny; lobes of fruiting calyx each expanded 4. Fruit without wings, subshrubs without spiny branches.......................... Suaeda

1. Leaves nor stems succulent.................................................................................... 6

...... 6. Fruits with long white silky hairs, plants easily

identified ...... 6. Fruits not silky hairy; branches sharply pointed at end (or spiny).................. 7

7. Fruit wings entire, often reddish; bark of older stems with white ridges... Grayia

7. Fruit wings

toothed, or fruits not winged but with tubercles, usually green

|

||||

|

Odiferous herbs or shrubs with leaves digitately divided, 3–7 leaflets; flowers slightly bilateral, 4-merous with separate sepals and petals; stamens 6, equal in length; Gynoecium syncarpous, two carpellate, ovary stipitate; fruits utricular, turgid to inflated. Family included by some in Capparaceae (JM1), or Brassicaceae. Isomeris also included in the genus Peritoma (JM2) or Cleome. Fruit inflated, bladder to ball-like.................................................................................... Isomeris Fruit not inflated, bilobed, similar to a peanut,............................................................... Wislizenia

|

||||

|

Herbs, shrubs or trees; leaves of woody plants usually deciduous, opposite, simple, generally recognized by arcuate pinnate veins impressed into the upper surface of leaves and often with parallel tertiary cross veins; flowers numerous in terminal umbrelliform clusters on branching scapes (cymose inflorescences), or condensed into heads surrounded by petal-like bracts; flowers 4–5 merous; stamens 4–10; gynoecium syncarpous, inferior, 2–3 carpellate, with axile placentation and 1 ovule per carpel; fruit: drupe. 13 genera, mostly northern hemisphere; 1 in Kern County. Cornus |

||||

|

Crossosomataceae (Rock rose family) Densely branched shrubs, or small trees; branches dichotomous, alternate or opposite, often terminally spinescent; leaves deciduous, alternate or opposite, often clustered, short petioled, entire to terminally 3-lobed (Apacheria); flowers solitary on pedicels, (3-) 4–5 (-6) parted, wide spreading or urn-shaped (Apacheria, Forsellesia pungens); sepals greenish or maroon in part (Apacheria, F. pungens), united below the middle into a short hypanthium around a thickened nectary disk, or without disk; petals white, separate, clawed; stamens 4 to many inserted around the edge of the disk, each opposite a sepal or petal, or united near base with the disk, or inserted below on the hypanthial tube ; gynoecium apocarpous, 1–5 (-9) carpels; fruit: apocarpous, follicular, camararilla (or camarilletum, not aggregate), ventrally dehiscent, or indehiscent; seeds 1, 2 or more (arillate), aril yellowish to white. Four genera (Sosa & Chase 2003), 12 species. Key to genera of Crossosomataceae Leaves with thickened petiole base; carpels sessile...... ............................. Forsellesia

Leaf petioles not thickened where attached to stem, carpels stipitate;

Elaeagnaceae (Oleaster family) Family easily recognized by the foliage of silvery fish-scale-like hairs; flowers in axillary racemes, 4-merous with a tubular hypanthium; stamens 4 or 8; stipules absent; gynoecium of one carpel with one ovule at the base; fruit: a pseudodrupe, the inner layer of the hypanthium differentiated into a stony layer (Elaeagnus), or an acrosarcum, the hypanthium becoming fleshy and berry-like (Shepherdia). 3 genera, 50 species, one in Kern County, Shepherdia.

|

||||

|

Ericaceae (Heath family) Ericoideae. Mostly evergreen (Kern Co.), or deciduous shrubs, or trees, rarely shrublets (Chimaphila) with simple alternate or decussate or whorled (“braided”) entire leaves, occasionally opposite (e.g., Kalmia) or shallowly toothed (e.g., Leucothoe); flowers (inflorescences) solitary to clustered from axils of leaves on pedicels or bracteate scapes (racemes), or in terminal branched to simple bracteate scapes (panicles, racemes), urn shaped, bell-shaped, bowl-shaped, or funnelform; calyx of mostly 5 distinct sepals, occasionally fewer, stamens often twice the number of sepals, usually 10, occasionally 8, 5 in the Kern Co. Rhododendron; petals mostly 5, united to nearly distinct; gynoecium of (2-4-) 5 (-10) united carpels (syncarpous) situated above the insertion of the petals, or below (Vaccinium) with a single style terminating in a slightly lobed stigma, ovary 4–10 locular, placentae axile or parietal and deeply intruded; fruit a berry, capsule, or drupaceous. The family Ericaceae, which is recognized to include parasitic or saprophytic herbs that do not produce chlorophyll, is a common component of the California chaparral and montane forests, but not in Kern County, where poorly represented. Manzanita (Arctostaphylos), for example, is most common in the southwest, Mt. Pinos region and in the Greenhorn Range. Notably absent are huckleberry-blueberry (Vaccinium) and mountain heather (Empetrum) that occur in the Sierra Nevada as far south as Tulare County. Empetrum also occurs in the San Bernardino Mts. Madrone (Arbutus), a characteristic component of the California "mixed evergreen forest" and reportedly common in San Luis Obispo County, does not reach Kern County. Salal (Gaultheria shallon), a low creeping shrub of coastal forests, is common in the northern part of the state, extends south to Santa Barbara County, and the related G. humifusa, known in the Sierra Nevada south to Tulare County, are also absent. These absentees are indicative of the oak woodland and desert scrub that has historically characterized much of the Kern County flora. Key to Genera of Ericaceae in Kern County:

Shrublets with single dull reddish stems <15 cm high, terminating

Much-branched shrubs or small trees with shiny red stems;

Sparingly branched shrubs or small trees with gray bark; flowers

|

||||

|

Euphorbiaceae (Spurge family) Plants variable in habit and leaves; herbs and succulents often juicy with white, yellow, orange, or red latex; hairs often present in woody plants, often branched at or above base; flowers usually small, unisexual on the same or different plants, with greenish sepals; petals usually lacking or in some genera deceptively appearing present by petal-like glands around a green hypanthium-like or cup-like structure, an involucre, referred to as a cyathium in which are many male flowers reduced to their barest essentials, a single stamen, or fascicles of stamens, up to 5 in number, each stamen with a tiny bract below the joint of its pedicel, and each cyathium with a single bare female flower—lacking perianth, which may have 3 bracts below its pedicel; gynoecium generally syncarpous, 3- carpellate, usually evident by the 3-lobed ovary, a good character clue to recognizing the family, each carpel with one ovule; carpels upon maturation usually breaking away from the central axis and opening longitudinally, thus, appearing capsular (septifragal) and schizocarpic, seeds arillate; indehiscent fruits also occur. A cosmopolitan family, >300 genera, 1200 species. As a general rule, plants with milky or colored latex are poisonous. The family has been and continues to be of intense pharmacological interest for its biological activity. Many active agents of Euphorbiaceae have carcinogenic properties, but the search for the exceptions, particularly in the genus Euphorbia, include those that have anticancer activity without carcinogenetic properties. Numerous species are reportedly used medicinally by many cultures. Low spreading subshrub; leaves simple, native ................................................................. Croton Tall erect shrubs with digitately divided leaves, introduced................................................. Ricinus

|

||||

|

Fabaceae (Pea family)

Herbs, shrubs, or trees; usually recognized by the alternate leaves pinnately or digitately divided, by the fruit “bean pod”, and by the flowers, either conspicuous by the colorful long stamens (Mimosa subfamily, Mimosoideae), or by their unequal 5 petals, slightly different in size and appearing nearly radial in the Senna subfamily (Casalpinoideae), or more commonly by the pea flower, with two joined oat like (keel) petals, surrounded by 2 lateral petal wings and topped by a petal headdress (banner), “Pea subfamily” (Faboideae); gynoecium usually of one carpel, a legume with ovules in two rows and with two sutures, which do not always open upon when mature. Key to Fabaceae genera in Kern County 1. Plants spiny.................................................. ........... ............................................. 2 1. Plants not spiny...................................................................................................... 7

2. Shrubs with

numerous erect broom-like stems, mostly leafless

2. Shrubs or trees

with wide spreading branches, often arching or

3. Leaves not stalked,

digitately divided into 3 leaflets, or leaves simple;

3. Leaves stalked,

pinnately divided into 3 or more leaflets; flower pink

4. Leaves with a

terminal odd leaflet (in the direction of leaf 4. Leaves lacking a terminal odd leaflet; plants not aromatic nor glandular................... 5

5. Plants with thorns in pairs; leaflets numerous, 14–34.................................... Prosopis 5. Plants with single thorns; leaflets <10...................................................................... 6

6. Stems all green,

photosynthetic; flowers yellow; common in

6. Stems brown,

except growth on current season ; flowers pink

7. Stems mostly green, often leafless............................................................................ 8 7. Stems brown, leaves conspicuous.......................................................................... 10

8. Stems round in

x-section, smooth, rush-like with scattered 8. Stems angled; leaves compound (3-foliate) ........... ................................................ 9

9. Fruit (pods) with

white shaggy hairs; leaflets broad elliptic with a

9. Fruit mostly

without hairs; leaflets narrow elliptic with inconspicuous

10. Leaves simple,

heart shaped or kidney shaped; flowers with red

10. Leaves pinnately or

digitately divided into numerous leaflets; petals white

11. Leaves digitately divided.............................................................................. Lupinus 11. Leaves pinnately divided........................................................................................ 12

12. Rhizomatous herbs, sometimes with shrubby habit,

forming local patches 12. Definitely shrub or tree; flowers fruit without hairs.................................................. 13

13. Shrubs with erect

stems terminating with a floral axis of yellow flowers 13. Trees with long dangling leaves and racemes of white flowers....................... Robinia

|

||||

|

Fagaceae (Oak family) Trees or shrubs with usually alternate leaves; flowers (inflorescences) with separate male and female clusters on the same plant (monoecious), males numerous in tassel-like hanging catkins, or in ball-like clusters; females solitary or few at base of catkins, or in separate axils, individually or collectively subtended by “cupule” that enlarges in the development of fruit; gynoecium of usually 3 united carpels with a 3 loculed ovary, positioned below the 3–7 sepals, or sepals not evident; styles as many as the carpels, separate. Fruit a glans (acorn), catoclesium or trymosum.

Fruit developing from a spiny involucre enclosing 1–3 pericarpia,

opening at Fruit (acorn) with a cupular involucre at base of pericarpium, cup scaly to tubercled.......... Quercus

|

||||

|

Grossulariaceae (Ribes)

Hydrophyllaceae (Waterleaf family, Boraginaceae in JM2, Namaceae in APG III) Herbs or shrubs; leaves usually alternate, often compound in herbaceous and subshrub species, or simple in the shrub species; flowers often clustered on terminal circinate (“scorpioid” or “helicoid”) shortly branched floriferous shoots from a main axis, occasionally solitary but then often on long curved or coiled pedicels, (4-) 5 merous; sepals partly united, mostly near base, the calyx lobes often narrow; petals more united, the corolla tubular or funnelform; stamens as many as corolla lobes, alternate with them; gynoecium syncarpous, 2 carpellate, superior with 2 distinct styles near stigmas or more commonly distinct from near ovary; ovary with deeply intruded parietal placentae, to the extent that some species become 2 locular; fruit capsular, opening dorsally (loculicidal capsule). Family recognized here as separate from the Boraginaceae, which is distinguished by the fruit divided into 4 separate seed units (mericarps); the four separate developing mericarps usually evident in flower, derived from two carpels in which each carpel transversely separates into two half carpels, comparable to a lomentum but a schizocarp as a result of the whole carpels also separating at maturity. This occurs similarly in drupaceous fruits (within the same family) in which the endocarp of a carpel divides into half-carpelled pyrenes. The Hydrophyllaceae includes two clades (Wiegend et al. 2014), proposed to be split into two families, one of which includes the shrub genera in Kern County, and the herbaceous Nama, classified in the family Namaceae.(APG III). Key to Hydrophyllaceae subshrub and shrub genera in Kern County

1.

Plants scarcely woody above base; leaves deciduous, often divided or

1.

Plants woody well above base; leaves evergreen, simple, serrated

(toothed)

2. Leaves uniformly

long narrow to sword-shaped, >10× longer than wide;

2. Leaves uniformly

narrow to broad elliptical, usually 3–10× longer than

|

||||

|

Lamiaceae (Mint Family) Herbs or shrubs, usually aromatic with quadrangular stems; leaves simple, opposite; flowers of united petals, usually divided into a lower 2-lobed portion (lower lip) and upper 3-lobed part (upper lip), or less often nearly equally lobed; the surrounding calyx 2-lipped to equally 5-toothed, often enlarging in fruit; stamens inserted on the floral tube in pairs, or one of the pairs not developing; gynoecium 2 carpellate, ovary 4-lobed, of 2 bilobed carpels, maturing as four separate mericarps (half carpels), or sometimes fewer than 4 mature. Fruit a bilomentarium (microbasarium Spjut 1994) in which the mericarps disperse as fruitlets, or a diclesarium in which the calyx forms a cover over the mericarps. Key to genera of Lamiaceae

1. Shrubs with

right-angle branching, sparingly leafy, not strongly aromatic;

1. Aromatic leafy

shrubs or subshrubs with erect stems; calyx not inflated 2. Flowers/fruits in terminal heads....................................................... Monardella

2.

Flowers/fruits in interrupted clusters, or in singles crowded along 3. Flowers/fruits in interrupted clusters subtended by bracts................................. Salvia

3. Flower/fruits

mostly singles crowded along a main axis, and/or with short

Loasaceae (Rock nettle family) Herbs or subshrubs, easily recognized by the nasty Velcro hairs, which may also sting (Eucnide), the leaves difficult to avoid and remove from clothing when collecting specimens; leaves alternate, or opposite below and alternate above, usually toothed or pinnately lobed (Mentzelia, Eucnide) similar to sword fern, or merely toothed to entire (Petalonyx); flowers yellow or white in our species, also orange, red or pink, (4-) 5 (-8) merous; stamens (5-) 10 or more numerous–>100, sometimes petal-like; gynoecium syncarpous, 1–5 (-7) carpellate, inferior, unilocular with parietal intruded placentae, rarely completely locular with axile placentation; fruit capsular, opening from apex part way (denticidal), or completely (septicidal or loculicidal), or irregularly (formanicidal, fissuricidal), or ±indehiscent (achene, utricle). ±20 genera, 200 species, primarily in seasonally warm and dry regions of the New World. Key to genera of Loasaceae

Young stems (twigs) brittle; leaves scabrous; (sandpaper like with

downward

Young stems herbaceous, fleshy; leaves (and stems) with stinging hairs,

|

||||

|

Malvaceae (Mallow family) Herbs, shrubs or trees; leaves generally alternate, maple-like, digitately lobed or divided and toothed along margins, 3–5-nerved from the base, with branched dendritic hairs (stellate hairs); flowers 5- merous (petals absent in some genera), axillary or terminal, solitary or in fasciculate branched (panicles) or simple scapes (racemes or spikes); sepals fused near base, petals usually clawed, stamens attached to base of petals, the filaments united into a columnar tube; few to many; gynoecium superior, syncarpous, of (-1) 5 (-40) carpels usually in well defined circle, with axile placentation, styles usually forked. Fruit a loculicidal capsule or schizocarp with variously ornamented monocarps, rarely a berry. ±240 genera, 4,200 species, cosmopolitan. Includes Fremontodendron formerly placed in Sterculiaceae.

1. Tree or large shrub; flowers (sepals only) yellow; fruit a

loculicidal

1. Shrubs or subshrubs; flowers pale pink to purple or white petals; 2. Carpels completely dehiscent by two sutures, one-seeded........... Malacothamnus

2. Carpels partially dehiscent or indehiscent

...... 3. Carpels 5–10, indehiscent, smooth to reticulate nearly

throughout, Meliaceae (Mahogany family) *Melia azedarach Linnaeus 1751. Cultivated tree native to Southeast Asia, leaves alternate, compound, divided twice into serrated leaflets, reported by Twisselmann to be occasionally spontaneous in the valley around old or abandoned dwellings. Moraceae (Fig family) *Ficus carica Linnaeus 1751. Domestic fig. A Mediterranean species planted frequently by early settlers for shade, but rarely survived (Twisselmann). *Maclura pomifera (Rafinesque 1817) C.N. Schneider 1906. Osage orange. Native to the Ozark region, but has been planted for fence rows and windbreaks in many regions of the U.S. Trees with separate male and female plants; fruit a fleshy composite ball of floral parts (sorosus), erroneously referred to a multiple fruit in much of the literature. Twisselmann reported a scattered colony of trees growing spontaneously along a drainage ditch east of Kern Lake near Hwy 99, 10 miles north of Mettlers Station. *Morus alba Linnaeus 1751. White mulberry. Reported by Twisselmann to be common along the Kern River near the Stockdale County Club. Tree, native to China; fruit a sorosus, the fleshy mass of berry-like fruitlets collectively falling, the juicy part of the fruitlets formed from perianth rather than the ovary. Myrtaceae *Eucalyptus camuldensis Dehnhardt Red gum. Tree; bark persistent near base; leaves evergreen, alternate, sword-shaped, aromatic; flowers red; fruit a pyxidium. Generally planted along roads as a windbreaker. Recognized to be well-established at the Old Headquarters on Tejon Ranch Conservancy, “Semi-Natural Woodland Stands” or “Eucalyptus groves” (MCV2; Magney Report 2010).Namaceae (Nama Family) Annual, subshrubs, shrubs, or trees; leaves alternate, deciduous or evergreen, usually well distributed above base, sometimes basally clustered, entire to toothed along margins. Flowers usually 5-merous, in terminal dichotomies or tirchotomies, rarely in head-like clusters (e.g., Nama rothrockii), shortly pedicelled or sessile, sepals united near base, the clayx deeply divided; petals united, the corolla mostly funnelform; androecium of equally or unequeal inserted stamens; gynoecium of 2 united carpels (syncarpous) with intruded placentae, perigynous or hypogynous, styles two or one shallowly to deeply divided; fruit a loculicidal capsule (Nama) or coccarium (separating septicidially and opening loculicidally). 4 genera, ~60 species, New World. Three genera in Kern County, two treated here, the third, Nama, mostly annuals, has one perennial or woody species, N. rothrockii A. Gray 1876, found mainly in the high Sierra Nevada and San Bernardino Mts., almost reaches Kern County on the Kern Plateau, occurring also at Sherman Pass, and commonly around Kennedy Meadows. Nama lobbii A. Gray 1864, included in McMinn’s California Shrubs, transferred by Greene to Eriodictyon in 1889, is treated in that genus in JM2; it occurs in northern California. Turricula, also included in Eriodictyon (JM2), has been kept separate here, while also recognized as a distinct genus by Molinari-Novoa (2016) and APGIII (Stevens; accessed June 2016).

Stems mostly simple and erect, often clustered at base, often densely

clothed

Stems occasionally branched, or if appearing simple then often with Oleaceae (Olive family) Shrubs or trees; leaves opposite, simple in fascicles (Forestiera), or trifoliate (Jasminum), or pinnately divided (Fraxinus, Jasminum); flowers terminal or axillary in simple or branched scapes, rarely solitary, radial; sepals and/or petals usually 4, or absent (Fraxinus, Forestiera), stamens 2(-4); gynoecium syncarpous of carpels 2, superior, locules 2, ovules 1-2(-4) per locule, axillary or pendulous, style 1, stigma 2-lobed or capitate. Fruit simple—drupe (Chionanthus with1 seed, Forestiera) or samara (Fraxinus), or schizocarpic—baccarium (Jasminum), or capsular—loculicidal capsule (Schrebera), pyxidium (Menodora); seeds 1–2. ±29 genera, 600 species. Key to Genera

Much-branched shrubs with fascicles of small simple, spoon a samara.................................................................................................Fraxinus

Onagraceae (Evening Priimrose Family) Mostly herbs, occasionally subshrubs, shrubs (Fuchsia) or trees (Hauya, S. Mex, C Am.) with alternate or opposite, or with both opposite and alternate leaves; flowers usually bisexual, 2 or mostly 4-merous (rarely 5-7 merous) with a elongated hypanthial tube from apex of ovary, the ovary thus inferior; sepals often reflexed from the tip of hypanthium; petals imbricate, valvate or convolute; stamens 4 (-5-6) or 8 (4 long stamens alternative with 4 short stamens); gynoecium 2 or 4 (-5) carpellate, 2 or 4 (-5) locular; fruit various, usually capsular opening along the dorsal suture or both ventral and dorsal sutures, or berry, or camara, or a simple catoclesium in which the ovary matures within the stem pith causing the stem to swell—appearing gall-like (Gongylocarpus rubricaulis) , or ovaries of many flowers of a terminal shoot collectively mature within the stem, the fruit (Wagenr et al. 2007, illus., G. fruticulosus)—resembling a racharium (Spjut 1994), perhaps best referred to as a catoclesarium. Generic concepts in Onagraceae have changed dramatically since Munz. The JM treatments did away with Zauschneria, placing it under Epilobium, but then JM2 (Wagner & Hoch) adopted the segregate genus Chamerion for fireweed and 7 other species, and further split the old Oenothera into more genera based on Wagner et al. (2007) and previous studies. Baum et al. (1994) stated that “morphological characters strongly support sect. Zauschneria, the species share long tubular hummingbird pollinated flowers found nowhere else in the genus.” It might be noted that the Baja California genus, Xylonagra, also has flowers similar to Zauschneria, but the seeds of Xylonagra lack the terminal patch of hair; instead, they develop a terminal wing, 4–5 mm, longer than seed body of 2.5–3.0 mm (Shreeve & Wiggins (1964), and the roots also are unusual in developing long lateral fleshy tubers (Spjut voucher specimens, 1979, 1986, NA, US, collected for antitumor screening, fleshy root marginally active in P-388 Leukemia, NCI CPAM 1982, and review of Baja California plants screened for antitumor activity); the genera classified in separate tribes (Wagener et al. 2007). The key below recognizes Zauschneria in contrast to JM1 and JM2. The genus Gaura, formerly distinguished in earlier California floras by indehiscent, football shaped, winged or ribbed, fruits with 1–2 ovules per carpel, has been included in Oenothera, formerly differentiated by having dehiscent, variously shaped, fruits with “many seeds.” Key to the California Genera of Onagraceae 1. Sepals persistent in fruit, plants of wet places................................... Ludwigia 1. Sepals gone in fruit; plants usually of dry or mesic places ............................. 2

2. Flower parts in 2's; fruit short, club-like with fish-hook hairs......... Circaea

2. Flower parts in 4's; fruit usually narrow and long (linear), or

shorter

3. Seeds with a persistent tuft of silky

hairs; sepals usually similar in color 3, Seeds with deciduous hair tuft or without hairs; sepals often green................. 5

4.

Herbs; flowers not fuchsia-like, petals clawed, not forming a long

tube,

4. Subshrubs; flowers fuchsia-like, petals narrowed into a funnelform

tube,

5.

Petals shallowly notched to deeply bifid; sepals erect; seeds often with

tuft

5.

Petals not bifid, of if bifid (some Clarkia) then sepals reflexed,

occasionally

6. Fruit erect to spreading, straight to recurved; seeds in 20 of 28

species

6. Fruit spreading and ascending (upcurved); seeds without hair tuft;

7. Stigma 4-lobed................................................................................................ 8 7. Stigma not lobed, often like a pin-head (capitate).............................................. 9

8. Leaves all basal, or with some cauline; petals not clawed;

fruit often

8. Leaves not concentrated at base of plant, usually well distributed

along

9. Fruit 2-loculed, erect, straight; flowers white; stems capillary;

leaves

9.

Fruit 4-loculed, often spreading, straight or twisted; flowers white or

yellow

10. Flowers white, pink or red, often terminally clustered or umbellate.................. 11

10. Flowers yellow, often fading red, solitary, or paired in leaf axils

along

11. Fruit sessile to shortly pedicelled; leaves not strongly basal,

mostly

11. Fruit pedicelled; leaves strongly basal, simple or divided with

12. Plants rather

low, flowers and leaves on relatively short erect stems, or

12.

Flowers on well-developed flowering

stems, leaves evenly distributed

13. Leaves clustered near apex of stem, with also the flowers; young

fruit 13. Leaves largely basal; fruit not as above.......................................................... 14

14. Fruit 1–1.5× longer than wide, four-winged, appearing star-shaped

14. Fruit >2× longer than wide, angled to rounded ............................................... 15

15. Fruit with a long sterile whip-like projection from a punching

bag-like

15. Fruit worm-like but quadrangular, usually curved, twisted

16.

Leaves

largely basal; stem leaves reduced or absent; largest leaf lobes

16. Stems

leafy; basal leaves usually much longer than wide, lanceolate,

17. Yellow petals with irregular to regular short red streaks

± close together

17. Yellow petals with one or two central to marginal spots near base or

18. Fruit quadrangular; seeds dull; leaves developed more near

18.. Fruit round in x-section; seeds glossy; plants leafy throughout,

Phrymaceae (Lopseed family) Herbs or shrubs with opposite leaves; floral calyx tubular, usually toothed, ribbed, keeled or winged along midrib, with petals mostly united, shortly lobed near apex, the lobes usually unequal in size, two-lipped, the upper lip three lobed, the lower lip two lobed, or rarely lobes equal (Mimulus sect. Mimulastrum included under Diplacus sect. Eunanus, Barker at al. 2012); stamens in two pairs, unequal in length. Gynoecium of 2 united carpels (syncarpous), ovules numerous, rarely 1, usually along axile placentae, less often parietal with intruded placentae, or sub-basal; style with a 2-lobed stigma. Fruit capsular, surrounded by a persistent or enlarging calyx, often narrowed to a thickened apical funnel that exceeds calyx, dehiscence often apicular, loculicidal and/or septicidal, or entire along both the septa and dorsal sutures (Diplacus clevelandii, Erythranthe), or incomplete (denticidal capsule, or camarium when dehiscing along one side of a carpel, or “upper suture”), or a carcerular diclesium (Mimulus sect. Oenoe, dehiscent after the plant has died and withered, Thompson 2005), or an achenoid diclesium (Phryma), or a white berry (Leucocarpus), the flesh of which is formed from placentae, thin skinned (epicarp), externally glabrous, sulcate along ventral suture. North America, South America, Asia, Africa, and Australasia. The shrubby species in Kern County belong to Diplacus. Erythranthe cardinalis, referred to as a subshrub by Barker et al. (2012), is not included; it is generally regarded as a perennial herb.

Polemoniaceae (Phlox family) Annuals, subshrubs or shrubs, usually <40 cm high; leaves relatively narrow, or the leaf segments of divided leaves narrow, filiform or needle-like, often ending in a sharp point, opposite, or alternate, closely overlapping in shrubby species, widely spaced, or developed more near base in herbaceous species; flowers usually terminal, appearing solitary on branched flower scapes (panicles, cymes), or leafy stems, or in head-like clusters, often subtended by spiny bracts, funnelform, 5-merous; sepals not always conspicuous, with green midribs partly united along hyaline membranes, which often rupture as fruit develops; petals usually colorful, often multicolored, funnelform, the lobes spreading; stamens with filaments attached at the same or different levels on the corolla tube; gynoecium syncarpous, 3 carpelled, 3-celled, style terminating with a 3-lobed stigma; fruit capsular, usually septicidal, loculicidal or septifragal, rarely a pyxidium or indehiscent. ~ 26 genera, 380 species concentrated in the western U.S., also Eurasia and South America. The classification of genera and species of the Polemoniaceae has been revised during the past decade according to molecular data that also identified morphological data for support, but not without considerable controversy (Grant 1998; Johnson et al. 2008). Leptodactylon has become a casualty of the new Polemoniaceae in which it has been terminated under Linanthus (Porter & Johnson 2000; Patterson & Porter in JM2–2011); however, their morphological distinction seems quite strong, at least in terms of size and habit. Fourteen species in JM2 (Linanthus) are small delicate annual herbs, largely under 20 cm, whereas the three former Leptodactylon species transferred to Linanthus are stiff prickly leaved shrubby plants up to 100 cm (L. pungens described in JM2 as reaching 30 cm can be up to 1 m in the White Mts.). There are no perennial herbs or intermediates (unless one reverts to the older classification of Grant (1998). While some genes may show Leptodactylon species nest with Linanthus (Johnson et al. 2008), one cannot help but wonder if there are other genes with greater phylogenetic significance as suggested by Grant (2003): “[A} molecular cladistic study generally utilizes one or only a few genes, whereas the phenotypic characters used in morphological systematics are expressions of scores or hundreds of genes. The molecular database is good as far as it goes but is very narrow. Molecular cladograms are being compared with phenotype based classifications in one plant group after another in the current literature. In any given group, one frequently finds congruence between cladogram and classification for some characters and incongruence for others. This is as expected on the considerations presented previously.” Grant (1998) had not only continued to recognize Leptodactylon as a distinct genus, but raised its taxonomic distinction to a higher taxonomic level as a tribe (Leptodactyloneae) that included Linanthus. The distinction of Leptodactylon is maintained here. Key to Genera of Polemoniaceae

1.

Stems densely leafy from base to flowers; leaves simple or digitately

2. Leaves

deeply digitately divided; stamens attached at the same

2. Leaves

simple; stamens attached at different levels in the corolla

1. Leaves

scattered along stems, pinnately divided; flowers Rhamnaceae (Buckthorn family) Shrubs or trees; leaves simple, alternate or less often opposite, either 1-veined without distinct lateral parallel veins (Ceanothus), or 3 main veins arising from a common basal point (Ceanothus), or with prominent lateral parallel arcuate veins arising along a mid vein (Frangula, Rhamnus); flowers often numerous but small in terminal and/or axillary branched flower scapes (inflorescences), pedicelled, usually not more than 5 mm, with a green nectary disc or hypanthium, which is sometimes circumscissile with the upper part falling away; sepals 4 or 5 sepals; petals not always present (absent in Rhamnus), same number as sepals when present, often forming a hood over the anthers, clawed at base, stamens each attached to base of petals; gynoecium syncarpous or schizocarpous, 2–3 carpelled, evident by the lobed or cleft style, usually with single ovule at base of each locule within the ovary, the basal placentation derived from axile placentation in which one (e.g., Ceanothus) or both margins of a septum is fertile. Fruit variable: a simple pericarpium differentiated internally by endocarp, a 3-celled pyrenarium (stone, Rhamnus, or endocarp separating into 3 pyrenes) or pericarp uniformly dry and differentiated by a wing (samara), or a fleshy anthocarp in which the pericarpium is covered by hypanthium as in the apple (pome), or schizocarpic, completely separating and opening along one or both sutures (coccarium, Ceanothus), or monocarps indehiscent and winged (samarium), or capsular and incompletely opening along outer layers (ceratium). Key to Rhamnaceae genera

1.

Upper surface of leaves three-veined at base, or veins obscure except

1. Leaves with conspicuous pinnate veins from base to apex; fruit drupaceous........ 2

2.

Leaves holly-like, thick, rigid, minutely sharply toothed along

2.

Leaves not holly-like, thin, entire to bluntly toothed along margins,

Rosaceae (Rose family) Herbs, shrubs or trees, the shrubs usually with alternate leaves, or leaves rarely opposite as in Coleogyne, often in fascicles (Coleogyne, Purshia), or variously divided into leaflets (Chamaebatia, Rosa, Rubus), or leaves simple and variously indented in upper half (Amelanchier, Cercocarpus), or distinctively three-lobed near apex (Purshia), or entirely simple with pimple like glands along the leaf margin near the base of blade or leaf stalk (petiole) in Prunus; stipules usually present. Flowers of separate petals usually attached to a green floral bowl or cup (hypanthium) in which one or more ovaries (with their styles and stigmas) develop freely or united with the hypanthium, the tube and/or other floral accessory structures often form much of the fruit in many genera—as exemplified by the hypanthium swelling and becoming fleshy in the apple (Malus) in which the core represents the mature ovary with characteristics of a capsule that contains the seeds, or in the rose (Rosa) multiple ovaries mature inside the fruiting hypanthium, or in the strawberry (Fragaria), multiple ovaries mature on a receptacle that enlarges and becomes fleshy, or in the mountain mahogany (Cercocarpus), the hypanthium splits as the style increases in length and becomes feathery in fruit; sepals usually5, appearing as lobes of the hypanthium. Stamens usually in sets of 5 or 10, or as many as 20. Gynoecium of separate (apocarpous; e.g. Rubus) or united (syncarpous; e.g, Malus) carpels, or of a single carpel (e.g., Prunus). The family Rosaceae is perhaps one of the most diverse families in morphology of all parts of the plant. The term “aggregated achenes” introduced by Phipps et al. in Flora North America (Vol. 9, 2015) in their descriptions of the fruit for the family, subfamilies and tribes of the Rosaceae, is confusing. The term aggregate fruit was first introduced by de Candolle (1813, 1819) as a formal name for fruit types of the infructescence that included the sorosus (mulberry), syconus (fig), and strobilus (cone)—and defined as a coalesence of mature ovaries (or seeds) with their associated floral parts or scales into a single seed dispersal unit. This ws preceded by L-C. Richard’s (1808) discoveries in his analysis of fruit morphology based on the pericarpium, and his recognition of the caryopsis (L-C. Richard 1811) that—up until then—was thought to be a naked seed. These discoveries quickly led to new fruit classifications (de Candolle 1813; Desvaux 1813; Mirbel 1813, 1815) which included many new names for fruit types that were not limited to the pericarpium fruit concept of L-C. Richard; see Spjut (1994) or web page, systematic treatment of fruit types, for complete reference citations and further examples. Prior to de Candolle (1813), the term aggregate was generally used in descriptions of infructescences (e.g., Linnaenus 1751); Gaertner 1788) as indicated by Spjut and Thieret (1989). De Candolle (1813, 1819) also introduced the term multiple, after Gaertner (1788), for a gynoecium composed of multiple free carpels (e.g., Cowania) that in fruit were collectively referred to as multiple fruit. However, Lindley (1831) confused their meanings. He (Lindley 1831) defined multiple fruit as one derived from one or more flowers, whereas the term aggregate he later (Lindley 1832) applied to both multiple and aggregate fruits. Additionally, it seems that Lindley avoided de Candolle’s (1813, 1819) fruit terms and meanings by citing other authorities, while he also reversed the definitions for the terms multiple fruit and aggregate fruit. His errors have been followed because it seems that English has become a dominant language despite the original meanings of these terms that continued to be employed in other countries where revised fruit classifications have been proposed and where English is not the main language, namely France, Russia, Germany, and Brazil. Although the term multiple fruit and its original meaning is employed in the non-English World, other terms have appeared for aggregate such as compound, anthocarp, pseudocarp, polyanthocarp, polythalamic, collective, confluent and others (Spjut & Thieret 1989). The term compound fruit, originating with Gaertner (1788), would seem preferable to aggregate because of the confusion that has arisen (Spjut & Thieret 1989); however, the confusion is still being perpetuated (FNA 2015). Aggregate literally means a coming together of different elements (or people for a purpose) as in the case of different parts of the inflorescence that collectively come together in fruit such as seen in the mulberry (Morus), whereas multiple (multiplied, multitude of people) refers to separate elements such as separate carpels within a single flower (or multiple people in a city going about their business in separate ways), which may independently disperse their seed (buttercup, Ranunculus), or they may unite in fruit into a single structure as exemplified by the sugar apple (Annona squamosa), the fruit of which is called a syncarpium (L-C. Richard 1798; Spjut & Thieret 1989; Spjut 1994). It may be further noted that Lindley (1819) clearly understood French as evident by his published English translation of L-C. Richard (1808), and that Gaertner’s (1788–1792) treatise of fruits, and others before him, were in Latin, and that Lindley has been a major reference for botanical terms and their meanings (Stearn 1983).Key to Genera of Rosaceae 1. Fruit dry, often brown in color..................................................................................................... 2 1. Fruit fleshy, often red in color...................................................................................................... 7 2. Leaves opposite; common desert shrub......................................................................... Coleogyne 2. Leaves alternate............................................................................................................................ 3

3. Leaves fern-like,

divided into leaflets, aromatic; plants low growing, 3. Leaves needle-like.................................................... ................................................ Adenostoma 3. Leaves blade-like, entire to toothed along margins to apex........................................................... 4

4. Leaves wedge-shaped and 3-lobed from apex.................................................................. Purshia 4. Leaves not as above.................................................................................................................... 5 5. Fruit with a long plumose style................................................................................... Cercocarpus 5. Fruit not with a plumose style....................................................................................................... 6

6. Flowers/fruits

terminal and numerous along short branches of

6. Flower/fruits