Niebla homalea

(Acharius) Rundel & Bowler

is a fruticose lichen first described by Acharius in 1810 as a species of Ramalina from

specimens collected on rocks in California, most likely

near Point Reyes in Marin County. The species is characterized

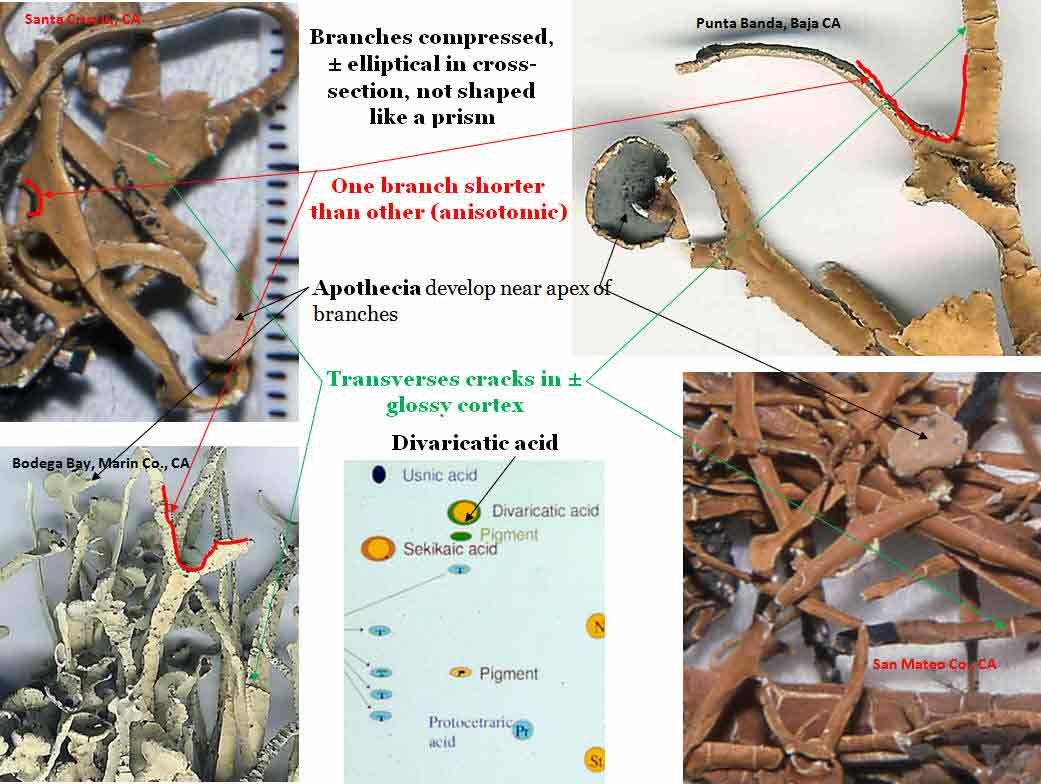

by a thallus containing divaricatic acid (with triterpenes) and by divided into

narrow

±cylindrical branches, which occasionally divide into

secondary branches of unequal length. The branch margins frequently twist 90°.

The cortex is usually glossy and transversely cracked at various intervals.

Niebla homalea is widely distributed from Point Navarro in

Mendocino County, California, to Isla Guadalupe and

slopes leading up to Mesa Camacho in the northern half of Baja California

peninsula.

A 6-loci phylogenetic tree of Niebla homalea (Spjut et

al. 2020) shows the species in

a large clade sister to N. turgida collected near San Antonio del

Mar. The California and Baja California specimens belong to

separate sister subclades and both include N. eburnea, which also

occurs elsewhere in the phylogenetic tree. The Baja California

subclades include other species identifications such as N.

testudinaria, N. juncosa var. spinulifera and N.

flagelliforma. These subclades represent separate cryptic species complexes in

California and in Baja California. Niebla homalea in a strict

sense may prove

endemic to Marin County; the putative type is from Point Reyes. BPP analysis delimited three species.

Most specimens were found associated with N. eburnea.

Jorna et al. (2021) reported they prepared a draft genome from a

specimen representing N. homalea collected from Sonoma

Coast State Park, Shell Beach. This draft has been published (Ametrano

in Duong et al. 2021).

The Niebla

homalea species complex is not the only example in which thalli

found growing in close proximity to one another show up in different

genomic clades as shown above for Niebla homalea specimens

collected on the Pt. Reyes Peninsula. This is commonly seen in

many if not most phenotypic species. Examples in the depside group

include

N. contorta,

N. dilatata,

N.

lobulata,

N. rugosa

and others. These complexes may be regarded to consist of cryptic

species, and/or in other cases cryptic hybrids where phenotypic

differences are evident in the sister clades. This may involve variation

in chemotypes such as seen with

N. effusa

and N.

palmeri. Hybridization seems the best explanation for

hybrid chemotypes between

N.

spatulata and N. contorta, especially where fusion

of thalli are evident.

In 1852, Montagne recognized Ramalina homalea

as belonging to a new genus he named

Desmazieria. Unfortunately,

this was similar to “Desmazeria” named earlier by Dumortier 1822 for a genus of grasses.

Although lichens have little in common with grasses, the

International Code of Nomenclature (ICN) allows only one

name, the later homonym by Montagne must be rejected unless conserved. Follmann (1976),

who apparently

discovered Dumortier's earlier name, stated that the names for

the two genera “do not sound sufficiently similar that they are likely

to be confused. Therefore, the genus name Desmazieria Mont.

can be retained.” However, Rundel and Bowler (1978) disagreed;

they created the substitute name Niebla.

Montagne's name for the one species was

clear, “Desmzieria

homalea Montag.” His description of the species

was followed by reference to synonyms that

included not only his Usnea ceruchis, but earlier synonyms “Borrera

ceruchis Ach.?” and “Ramalina ceruchis” De Notaris (1846). Since Montagne (1852)

recognized only one species, the type has to be Desmazieria

homalea (Acharius) Montagne 1852 (ICBN Art. 7.1–7.4), which is now Niebla homalea (Acharius) Rundel & Bowler

1978.

Subsequently, Rundel and Bowler (in Rundel et al. 1972), recognized two

additional species under the illegitimate Desmazieria,

Niebla sensu Spjut (1995, 1996), later legitimized in Niebla

(Rundel & Bowler 1978), N. josecuervoi and N. pulchribarbara

from thalli growing around Bahía

de San Quintín,

Baja California. However, their 'beautiful' lichen

N.

pulchribarbara was subsumed under

N. josecuervoi, (Bowler and

Marsh 2004) in further honor of their field assistant who the lichen was

named after. Thus, only three North American species of Niebla sensu Spjut were

recognized by Bowler and Marsh (2004; N. homalea,

N.

isidiaescens, N. josecuervoi).

It

is interesting to note that Vermilacinia laevigata (Niebla

laevigata, Bowler et al. 1994) had been overlooked

for many years because of its superficial resemblance to N. homalea. Mason Hale's

(Hale & Cole 1988) Lichens of California included a color photograph of Vermilacinia laevigata referred to as N. homalea despite knowing that it might

potentially be V. halei Spjut (unpublished) from his review of Spjut's manuscript and

numerous specimens at the Smithsonian Institution with this name,

and from Spjut's review of his manuscript for which

he remarked that his Niebla names were probably not correct.

Unfortunately, V. halei Spjut in editus had to be retracted from publication, because Bowler et

al. (1994) published their name (N. laevigata) as Spjut (1996) was in

press.

Howe (1913), who monographed the North American Ramalina, was

obviously aware of the morphological differences between Vermilacinia

and Niebla—by his remark that he considered the chondroid

strands of Ramalina (Niebla) “almost of generic

importance”—and perhaps would have treated them in different genera had

he had the chemical tools of modern lichenology such as microcrystal

tests (1930's–) and thin-layer-chromatography (TLC, 1950's–).

Additionally, it appears that misidentification of an unknown triterpene

(T3, Spjut 1996), referred to as methyl 3,5 dichlorolecanorate by Rundel

& Bowler on their chemical annotation labels of specimens at the US

(Smithsonian Institution, herbarium), and the lack of clear reference to

the key chemotaxonomic diterpene in Vermilacinia tuberculata by Riefner

et al. (1995, as Niebla tuberculata), which was not clearly

distinguished from zeorin, may

explain their inability to accept Vermilacinia (Spjut 1995).

Another problem is that chemical differences in these lichens are not

distinguishable by chemical spot tests, introduced by Nylander during

the 1860's (Molnára & Farkas 2010) at which time lichenologists

considered lichen species based on chemical differences nonsense,

although some mycologists today, who review NSF grants, still hold that

view

Triterpenoids in Niebla homalea include novel stictanes, named

nieblastictanes and nieblaflavicanes (Zhang

et al. 2020; Diaz-Allen et al. 2021). Presumably these or similar triterpenoids are

found in all depside species of Niebla.

Penicillium aurantiacobrunneum was cultured from the specimen

collected at Point Reyes (17806). Isolated from this fungal associate

were 4-epi-citreoviridin, 15 auransterol, and two analogues of

paxisterol, along with two known metabolites (Tan

et al. 2019). Additional studies continue on paxisterol; see

under Tan et al. (2019).

Among the related species that contain divaricatic acid, N.

testudinaria and N. eburnea are the

most difficult to distinguish from N. homalea. Their differences

are summarized in the following table.

|

|

N. homalea |

N. eburnea |

N. testudinaria |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Branching general |

Anisotomic. |

Anisotomic. |

Isotomic. |

|

Terminal bifurcate

branches |

Usually not evident. |

Usually not evident. |

Frequent. |

|

Branch shape lengthwise |

Sublinear. |

Variable. |

Variable. |

|

Branch shape cross-section |

Elliptic. |

Elliptic. |

Elliptic, prismatic, or

±4-angled. |

|

Branches twist |

Frequent between base and apex. |

Half twist near base and apex. |

Frequent between base and apex. |

|

Branch margin |

Usually well-defined, acute. |

Rounded to acute, usually thickened, wrinkled in upper half

of thallus. |

Variable. |

|

Cortex |

Glassy, transversely cracked at various intervals. |

Creamy frosting or like a glazed donut, irregularly

transversely cracked or pleated. |

Dull, transversely cracked and reticulate ridged

between margins. |

|

Apothecia |

Subterminal on short branch-like segments, often perpendicular to

branch margin. |

Usually subterminal, often in plane with the branch. |

Usually absent, subterminal in type, elevated from main

branch by a short flattened lobe. |

It

may also be noted that both Nylander (1870) and Howe (1913) distinguished Niebla

testudinaria from N. homalea (under Ramalina). Their studies were more

than just casual; both lichenologists monographed Ramalina. Spjut

(1996) further clarified the differences between these species by

recognizing N. eburnea, and others with divaricatic-acid and

depsidones.

The problem

in dealing with the variation in Niebla is that there are many

species in the genus that need to be sorted out before any of them can

be clearly identified. Mason Hale once asked if

there were new species at every new location I encountered Niebla. The Niebla and Vermilacinia complexes

comprise

one of the most variable and poorly understood lichen groups on the

planet. They are also vanishing; for example, a morphological variant of

N. disrupta,

distinguished in part by having sekikaic acid, was collected by Riefner

in 1986 on rocks just above the littoral around Morro Bay where he had

reportedly found it to be abundant, but I did not see any Niebla

around Morro Bay when I looked for it in Feb 2011. Additionally, conservative taxonomic views on Niebla

(Bowler & Marsh 2004)

would seem to mask many rare species of Niebla

and Vermilacinia that may need protection.

References

Acharius, E. 1803.

Methodus qua omnes detectos lichenes. Stockholm.

Acharius, E. 1810. Lichenographia

universalis. Gottingen.

Ametrano C, Y Sun, I DiStefano, S Huhndorf,

H. Thorsten Lumbsch, and F Grewe. 2021. Draft Genome of Niebla homalea. In:

Duong TA, J Aylward, CG Ametrano, B Poudel, QC Santana, PM Wilken, A

Martin, KS Arun‑Chinnappa, L de Vos, I DiStefano, F Grewe, S Huhndorf, H

Thorsten Lumbsch, JR Rakoma,, B Poudel, ET Steenkamp, Y Sun, MA. van der

Nest, MJ Wingfeld, N Yilmaz, and BD Wingfeld.

2021. IMA Genome - F15. Draft genome assembly of Fusarium pilosicola,

Meredithiella fracta, Niebla homalea, Pyrenophora teres

hybrid WAC10721, and Teratosphaeria viscida.

IMA Fungus. Open Access

Bory, St-V., de. 1828. Cryptogamie. In

Voyage autour du monde, par M. L. I. Duperrey, capitaine de Frgate.

Arthus Bertrand, Paris.

Bowler, P. A, R. E.

Riefner, Jr., P. W. Rundel, J. Marsh & T.H. Nash, III. 1994. New species

of Niebla (Ramalinaceae) from western North America. Phytologia

77: 23-37.

Bowler, P. A.

and

J. Marsh. 2004. Niebla.

Lichen Flora of the Greater Sonoran Desert 2: 368–380.

De Notaris CG, 1846. Prime linee di una nuova

disposizione de Pirenomiceti Isterini. Giornale Botanico Italiano 2,

part I, fasc. 7-8: 5-52.

Diaz-Allen, C., R. W. Spjut, A. Douglas Kinghorn, and H. L. Rakotondraibe. 2021. Prioritizing natural

product compounds using 1D-TOCSY.

Trends in Organic

Chemistry 22: 99-114.

Follmann, G. 1976. Zur

Nomenklatur der Lichenen. III. Uber Desmazieria Mont.

(Ramalinaceae) und andere kritische Verwandtschaftskreise. Philippia

3:85-89.

__________1994.

Darwin's “lichen oasis” above Iquique, Atacama Desert rediscovered.

International Lichenological Newsletter 27: 23-25.

Hale, M. E. Jr. and M.

Cole. 1988. Lichens of California. Univ. California Press.

Howe, R.H., Jr. 1913.

North American species of the genus Ramalina.

Bryologist 16:

65-74.

J Jorna, J Linde, P Searle, A Jackson,

M-E Nielsen, M Nate, N Saxton, F Grewe, M de los Angeles Herrera-Campos,

R Spjut, H Wu, B Ho, S Leavitt, T Lumbsch. Species boundaries in the

messy middle -- testing the hypothesis of micro-endemism in a recently

diverged lineage of coastal fog desert lichen fungi. Submitted March 29,

2021, to Ecology and Evolution, open access to ms,

Authorea. In this study, only Niebla species were assessed

employing RAD –sequencing.

Krog, H. & H. Østhagen.

1980. The genus Ramalina in

the Canary Islands. Norwegian J. Bot. 27:255-296.

Meyer, G. F. W. 1818.

Primitiae Florae Essequeboensis.

Gottingae: Sumptibus H.

Dieterich.

Molnára, K. and E. Farkas. 2010.

Current results on biological activities of lichen secondary

metabolites: A review. Z. Naturforsch. 65 c, 157–173.

Montagne, D.M. 1834.

Description de plusierus nouvelles espces de cryptogames dcouvertes par

M. Gaudichaud dans l'Amrique mridionale. Ann. Sci. Nat. Sr. 2, 2:369-373

& pl. 16, fig. 1.

__________. 1844.

Botanique. In Voyage de la Bonite, C. Gaudichaud & A. Bertrand, eds. Roi,

Paris.

__________. 1852.

Diagnoses phycologicae. Ann. Sci. Nat. Sr. 3, 18, 302-319.

Nylander, W. 1870.

Recognitio monographica Ramalinarum. Bull. Soc. Linn. Normandie, Sér. 2,

4:101-181.

Rakotondraibe H L R, Spjut R W, Addo E M. 2024.

Chemical Constituents Isolated from the Lichen Biome of Selected Species

Native to North America. Prog Chem Org Nat Prod. 2024;124:185-233. doi:

10.1007/978-3-031-59567-7_3. PMID: 39101985.

Rundel, P.W., P.A. Bowler & T.W. Mulroy.

1972. A fog-induced lichen community in northwestern Baja California,

with two new species of Desmazieria. The Bryologist 75: 501–508.

Rundel, P.W. and P.A. Bowler,

1978. Niebla, a new generic name for the lichen genus Desmazieria (Ramalinaceae).

Mycotaxon 6:497-499.

Sérusiaux, E., P. Van den Boom, and D. Ertz.

2010. A two-gene phylogeny shows

the lichen genus Niebla (Lecanorales) is endemic to the New World

and does not occur in Macaronesia nor in the Mediterranean basin. Fungal Biology 114:

528-37.

Sipman, H.J.M. 2011.

New and notable species of

Enterographa, Niebla, and Sclerophyton s. lat. from

coastal Chile.

Bibliotheca Lichenologica 106: 297-308.

Spjut, R. W. 1995. Vermilacinia (Ramalinaceae,

Lecanorales), a new genus of lichens. Pp. 337-351 in Flechten

Follmann; Contr. Lichen. in honor of Gerhard Follmann, F. J. A. Daniels,

M. Schulz & J. Peine, eds., Koeltz Scientific Books, Koenigstein.

_________. 1996. Niebla and Vermilacinia (Ramalinaceae)

from California and Baja California. Sida, Botanical Miscellany 14:

1–207, 11 plates.

Stevens, G. N. 1988. The lichen genus Ramalina in

Australia. Bulletin of the

British Museum (Natural History), Botany Series 16: 107–223.

Tan C.Y., Wang F., Anaya-Eugenio G.D., Gallucci J.C., Goughenour K.D.,

Rappleye C.A., Spjut R.W., Carcache de Blanco E.J., Kinghorn A.D.,

Rakotondraibe L.H. (2019) α-Pyrone and sterol constituents of

Penicillium aurantiacobrunneum, a fungal associate of the lichen

Niebla homalea. J. Nat. Prod. 82:2529-2536.

Tan CY. 2020. Identification and Dereplication of Bioactive Secondary

metabolites of Penicillium aurantiacobrunneum,

a Fungal Associate of

the

Lichen Niebla homalea. Ph.D. Dissertation, The Ohio State

University.

Anaya-Eugenio G.D., Tan C.Y., Rakotondraibe L.H., Carcache de Blanco E.J.

(2020) Tumor suppressor p53 independent apoptosis in HT-29 cells by

auransterol from Penicillium aurantiacobrunneum. Biomed.

Pharmacother.

127:110124. DOI: 10.1016/j.biopha.2020.110124.

Yamano,

Y. and L. H.

Rakotondraibe. 2022.

Understanding

the Biosynthesis of

Paxisterol in Lichen-Derived Penicillium aurantiacobrunneum

for

Production of Fluorinated Derivatives. Molecules Mar 2;27(5):1641

Aldrich L.N., J. E. Burdette, E. Carcache de Blanco,

C. C. Coss, A. S. Eustaquio,

J. R. Fuchs, A. Douglas Kinghorn, A. MacFarlane, B. K. Mize, N. H. Oberlies,

J. Orjala, C. J. Pearce, M. A. Phelps, L. H.

Rakotondraibe, Y. Ren, D. Doel

Soejarto, B. R. Stockwell, J.

C. Yalowich, and X. Zhang. 2022. Discovery of

Anticancer Agents of

Diverse Natural Origin. J. Nat. Prod. 85 (3): 702-719

DOI: 10.1021/acs.jnatprod.2c00036.

Trevisan, V. G. 1861. Ueber

Atestia eine neue Gattung der Ramalineen aus Mittel-Amerika. Flora

4:49-53.

Y.

Zhang, CY Tan, RW Spjut, JR Fuchs, AD Kinghorn, LH Rakotondraibe. 2020

(Oct). Specialized metabolites of the United States lichen Niebla

homalea and their antiproliferative activities. Phytochemistry 180,

112521. In this paper, the type locality for N. homalea is

determined to be most likely Point Reyes in Marin County, California,

collected by Archibald Menzies in November 1792. Triterpenoids in

Niebla homalea were new, and named nieblastictanes, the name given

in reference to the genus name, Niebla, and stictanes, which are

related triterpenoids, previously discovered in unrelated South American

lichens belonging to the genus Sticta.