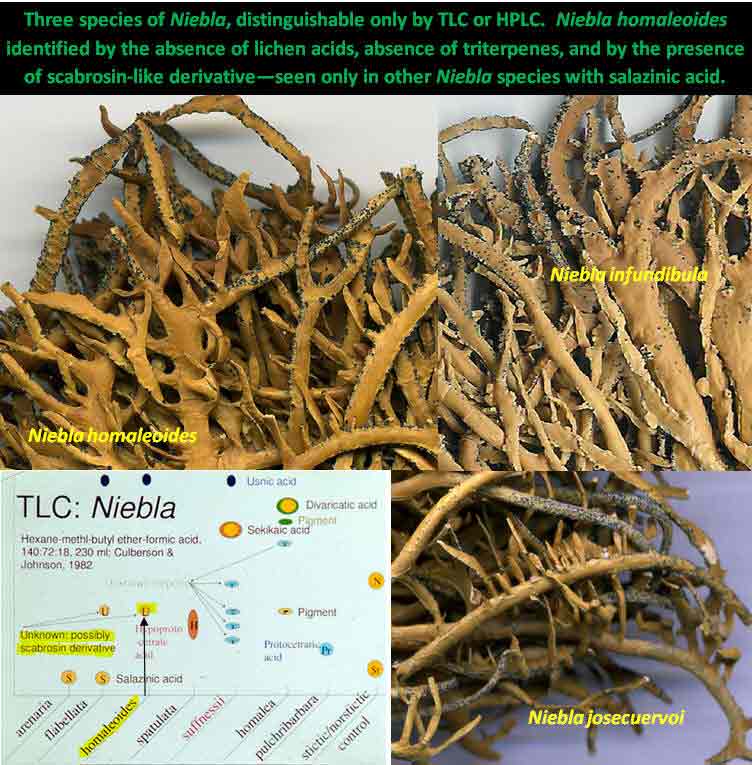

Niebla

homaleoides is a rare species of lichen known only from three locations in Baja

California; two are from ridges south of Punta Negra, and a third is from a

rocky peninsula near sea level at Punta Cono. The type locality is

a large rock pile on a ridge where collected in close

association with N. josecuervoi and

N. infundibula. An

attempt was made in the field to sort these (May 1986); however, it was not

until later that it was concluded that

they could only be distinguished by their lichen substances as a result of using

thin-layer chromatography (TLC).

Their close resemblance to each other is clearly evident in the image above that

includes the TLC graphic. They are similar in overall size and branching,

have the same sublinear branch shape, have the same glossy and color

cortical features, have prominent large and abundant pycnidia on upper branches, all lack reticulate ridging, and all

show similar development in branchlets including shape and

size—somewhat elliptical and flattened—rarely seen in other

species with cylindrical branches. This seems more than coincidental considering the wide range of

morphological variation

in Niebla observed elsewhere on the ridge and generally in Baja

California (e.g., see associated species with reference to collection numbers

under N. caespitosa).

For example,

Niebla josecuervoi, which has secondary

metabolites of salazinic acid, occasionally with a scabrosin derivative and

consalazinic acid,

usually has a reticulately ridged cortex, evident in all 12 other specimens shown on

the WBA page. Did a spermatium from N. homaleoides contribute to a

spore progeny thallus of N. josecuervoi originating from an apothecium of N.

josecuervoi?

Niebla infundibula, another

relatively rare lichen known from this location, shows similar hybrid

characteristics.

Did a spermatium from N. homaleoides contribute to a spore progeny

thallus of N. infundibula originating from an apothecium of

N.

infundibula? Other specimens of N. homaleoides

from the same ridge and from Punta Cono have more flattened blades, which may be

characteristic of its true form. In the higher plant world such blending

of character traits among three species would be viewed as evidence of

introgression. Perhaps, secondary chemical substances in Niebla are allelopathic

towards related species (Molnára & Farkas 2010) in which case N.

homaleoides lacking in secondary metabolites is less competitive and more freely hybridizes?

Nonetheless, Niebla

homaleoides is identified by its lack of key lichen substances.

Its chemical relationship is

clearly allied to the salazinic-acid species subgroup by the

presence of an unidentified pigment thought to be a scabrosin derivative, and further linked to the Depsidone

Species Group of Niebla by the absence of triterpenes (Spjut 1996).

This pigment has been found in N. effusa,

N. flabellata,

N. marinii, and N. josecuervoi.

Bowler and Marsh (2004) failed to account for the

chemical relationships when they

erroneously placed Niebla homaleoides in synonymy with

N. homalea (divaricatic

acid); i.e. in following their taxonomic scheme they should have lumped it with

N. josecuervoi. Just because N. homaleoides does not react

to p-phenylenediamine (PD-) does not mean

that it is related to other species that are PD-. The

resemblance to N. homalea is seen in the blade morphology in the one

specimen from Punta Cono. The relationship of N. homaleoides to the depsidone group is

also evident by the pycnidia that develop at the tips of the spine-like

branchlets, some of which are shortly bifurcate.

Chemically deficient thalli in the genus Niebla occur at one other

location, Arroyo Sauces for which a specimen is shown above. It

differs from N. homaleoides in having more flattened lacerated

branches as in

N. spatulata. This lacerated branch form was also collected at Punta Cono. Their similar

morphology at two disjunct locations would seem to represent another

acid-deficient species, referred

to as

Niebla sp. undescribed, shown above for the one from Arroyo Sauces.

The phylogeny of Niebla homaleoides might be assessed from two

acid-deficient specimens collected by Spjut and Sérusiaux from the

Vizcaíno Peninsula; however, only ITS was employed, and only one of the

two specimens showed a difference of a single mutation in the

N.

spatulata complex. Acid deficient thalli had not been reported

by Spjut (1996) from the Vizcaíno Peninsula, although he

identified four specimens in the field as N. homaleoides based on

stretched marks on the cortex, two of which confirmed by TLC.

Additional

Reference Cited:

Diaz-Allen, C., R. W. Spjut, A. Douglas Kinghorn, and H. L.

Rakotondraibe. 2021. Prioritizing natural product compounds using

1D-TOCSY. Trends in

Organic Chemistry 22: 99-114.

Molnára, K. and E. Farkas. 2010.

Current results on biological activities of lichen secondary

metabolites: A review. Z. Naturforsch. 65 c, 157 – 173.

Further References: See

Niebla.