Niebla fimbriata

is a fruticose lichen occurring infrequently along the Pacific Coast of the Baja California

peninsula from

Punta Blanca north to San Antonio del Mar and the Channel Islands in California. It appears

most common in the Chaparral-Desert-Transition (CDT) between San Quintín and Cabo Colonet, especially

on lava rubble

of mesas such as east of

San Antonio del Mar, the type locality where it may be found with depsidone species,

N. josecuervoi

(salazinic acid), N. effusa (salazinic

acid), and N. pulchribarbara

(protocetraric acid).

Niebla

fimbriata is characterized by having sekikaic acid with triterpenes,

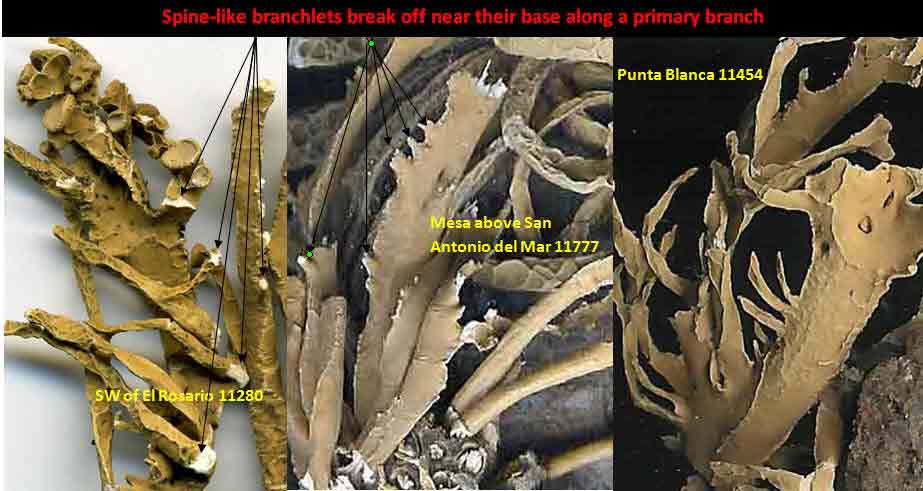

occasionally with both sekikaic acid and divaricatic acid, and by the wind-swept spine-like (fimbriate

or fringed) branchlets along a primary branch, all spreading nearly at right

angles,

±

in the same direction.

The fragmentation branchlets are rather brittle, easily breaking off near the main branch. The

fragile cortex is often dark olive green with frequent dimples or ripples, in contrast to

the leathery, turgid, pale yellowish green cortex of

N. suffnessii without basal dark pigmentation

and without differentiation of fragmentation branchlets.

Specimens of Niebla

fimbriata from the Channel Islands were included by their pinnatifid

branching but differ by less defined branch margins with the

intra-marginal cortical surface appearing more

strongly rugose. These features appear to intergrade with Channel

Island thalli identified

N. siphonoloba, a species generally

distinguished by its small tufts of simple tubular basal branches.

Judging from DNA phylogeny of the Baja California specimens, the Channel Island

specimens are likely to belong to other species, possibly

N.

dactylifera, currently regarded endemic to San Nicolas Island. Thalli

collected near Punta Canoas appear to intergrade with

N. suffnessii.

In Baja California,

Niebla fimbriata often appears similar to N.

juncosa var. spinulifera, which differs by having

divaricatic acid. Its branchlets appear less differentiated, ascend rather than

diverge widely from the main branch.

The phylogeny of Niebla fimbriata is problematic by appearing

polyphyletic in relationship to other phenotypic species included

(associated) within its sekikaic acid group and sister groups. Species

repeatedly associated with N. fimbriata are

N. lobulata,

N. aff. palmeri,

N. palmeri, and N. siphonoloba.

In view of Spjut et al. (2020) and Jorna et al. (2021), they can be referred to as species complexes by their phylogeographic

relationships. For example, in the CDT, they have been

collected together near Punta Colonet, San Telmo, San Antonio del Mar,

San Quintín, and Punta Baja (Spjut et al. 2020; Jorna et al. 2021).

Both BPP and Stacey methods applied by Spjut et al. 2020 (Suppl. files S

3, S5) delimited two species for N. fimbriata and two for N.

palmeri, four for N. lobulata, and one each for N.

siphonoloba and N. suffnessii; the latter two represented by

specimens only from their type locality near Cerro Elephante on

the Vizcaíno Peninsula. In view of their phylogeny in Spjut et al.

(2020, Fig. 7), combined with data in Jorna et

al. (2021), which included seven topotypes for N. lobulata, in

three clades, and one additional topotype in a sister clade of

unresolved species and another sister subclade with one specimen from the Vizcaíno Peninsula sister to N.

suffnessii, these are cryptic species complexes within which cryptic species

can be recognized in those phylogenies that include topotypes.

In

a narrowest sense,

N. fimbriata appears supported by a topotype, 17012-4670

(Spjut et al. Fig. 7), if epitypified by that specimen from San Antonio del Mar

since it appears monophyletic in a basal subclade sister to

subclade of sekikaic acid species complex (N. aff. fimbriata,

atypical N. lobulata (not from type locality), N. palmeri)

within a "terminal" sekikaic acid clade to a divaricatic acid clade.

All specimens differ in their triterpenes. However, BPP and Stacey

analyses may not support this division, only a broader subdivision

(larger clades) in which N. aff palmeri replaces N.

palmeri in the association of cryptic species. Niebla

aff. fimbriata 17009 also appears to be a hybrid.

It remains to be determined

whether atypical specimens identified N. siphonoloba and N.

palmeri can be distinguished from N. fimbriata by DNA to

correspond to their phenotypic characteristics. For now they

appear as cryptic hybrids, or allasomorphs, species that exhibit

different morphotypes. It may be noted that

N.

flagelliforma (divaricatic acid species) in Fig. 7 of Spjut

et al. (2020) is identified N. fimbriata in their Suppl. data S3

where correctly identified.

For more discussion

and reference materials see Introduction to Niebla